Training Emulators for Chaotic Dynamics

This popular summary is adapted from a blog post written for the UChicago Data Science Institute.

Chaos is everywhere, from natural processes—such as fluid flow, weather and climate, and biology—to man-made systems—such as the economy, road traffic, and manufacturing. Understanding and accurately modeling chaotic dynamics is critical for addressing many problems in science and engineering. Machine learning models trained to emulate dynamical systems offer a promising new data-driven approach for developing fast and accurate models of chaotic dynamics. However, these trained models, often called emulators or surrogate models, sometimes struggle to properly capture chaos leading to unrealistic predictions. In our recent work published at NeurIPS 2023, we propose two new methods for training emulators to accurately model chaotic systems, including an approach inspired by methods in computer vision used for image recognition and generative AI.

Machine learning approaches that use observational or experimental data to emulate dynamical systems have become increasingly popular over the past few years. These emulators aim to capture the dynamics of complex, high-dimensional systems like weather and climate. In principle, emulators will allow us to perform fast and accurate simulations for forecasting, uncertainty quantification, and parameter estimation. However, training emulators to model chaotic systems has proved to be tricky, especially in noisy settings.

One key feature of chaotic dynamics is their high sensitivity to initial conditions which is often referred to colloquially as the “butterfly effect”: small changes to an initial state—like a butterfly flapping its wings—can cause large changes in future states—like the location of a tornado. This means that even a tiny amount of noise in the data makes long-term forecasting impossible and precise short-term predictions very difficult. Accurate forecasts of chaotic systems, like the weather, are fundamentally limited by the properties of the chaos. If this is the case, should we simply give up on making long-term predictions?

The answer is both yes and no. Yes, even with machine learning, we will never be able to predict whether it will rain in Chicago more than a few weeks ahead of time (Sorry to all the couples planning outdoor summer weddings!). No, we should not give up completely because, while exact forecasts are impossible, we can still make useful statistical predictions about the future, such as the increasing frequency of hurricanes due to climate change. In fact, these statistical properties—collectively known as the chaotic attractor—are precisely what scientists focus on when developing models for chaotic systems.

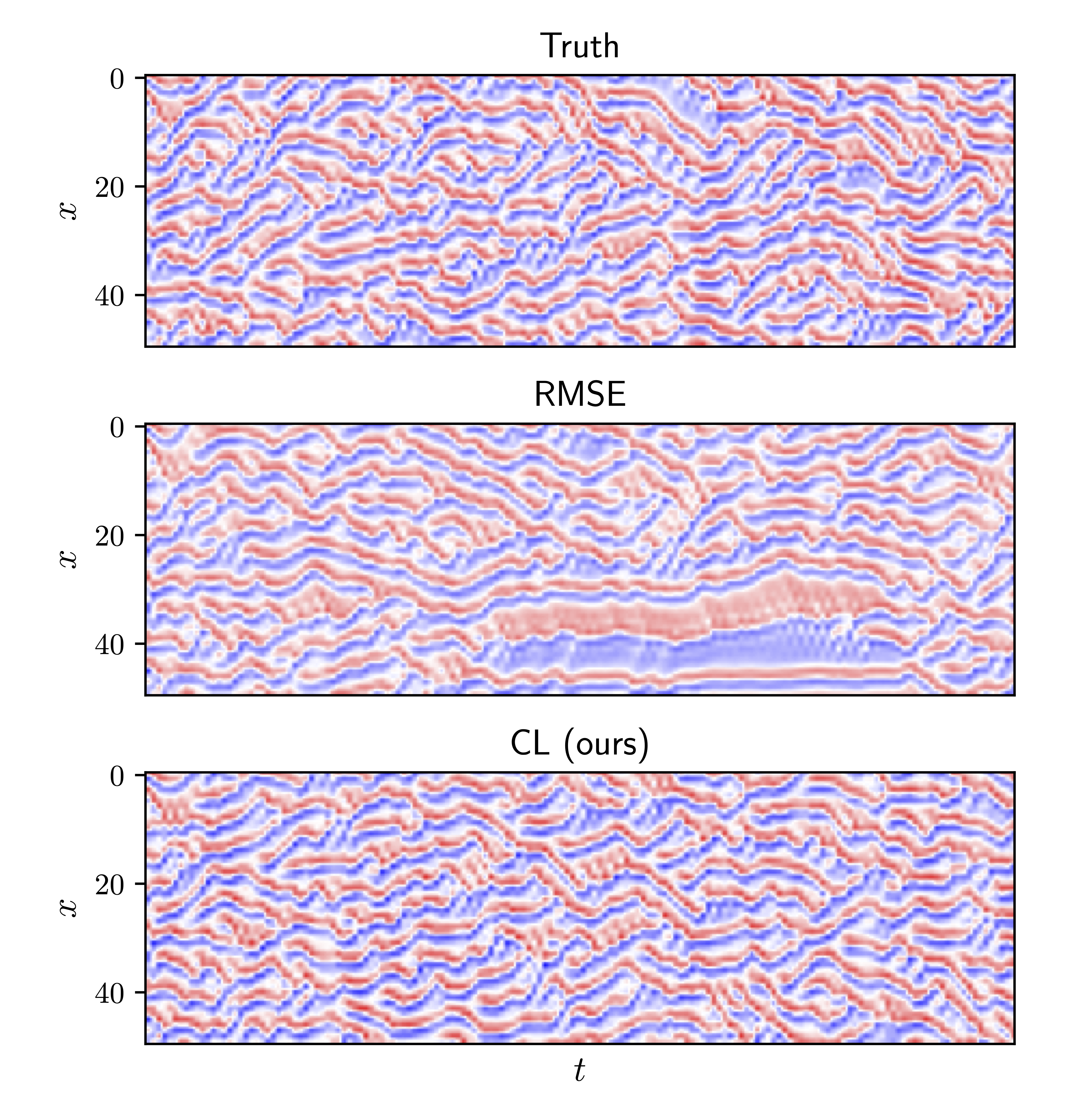

Despite these well-known properties of chaotic dynamics, most current approaches for training emulators still focus on short-term forecasting metrics such as the root mean squared error (RMSE). For extremely clean data with high-resolution measurements, the standard training methods are sufficient to learn the correct dynamics since chaotic systems are, after all, deterministic. However, when using noisy or low-resolution data, which is the norm in real-world applications, these training methods often produce emulators that fail to capture the correct long-term statistical behaviors of the system.

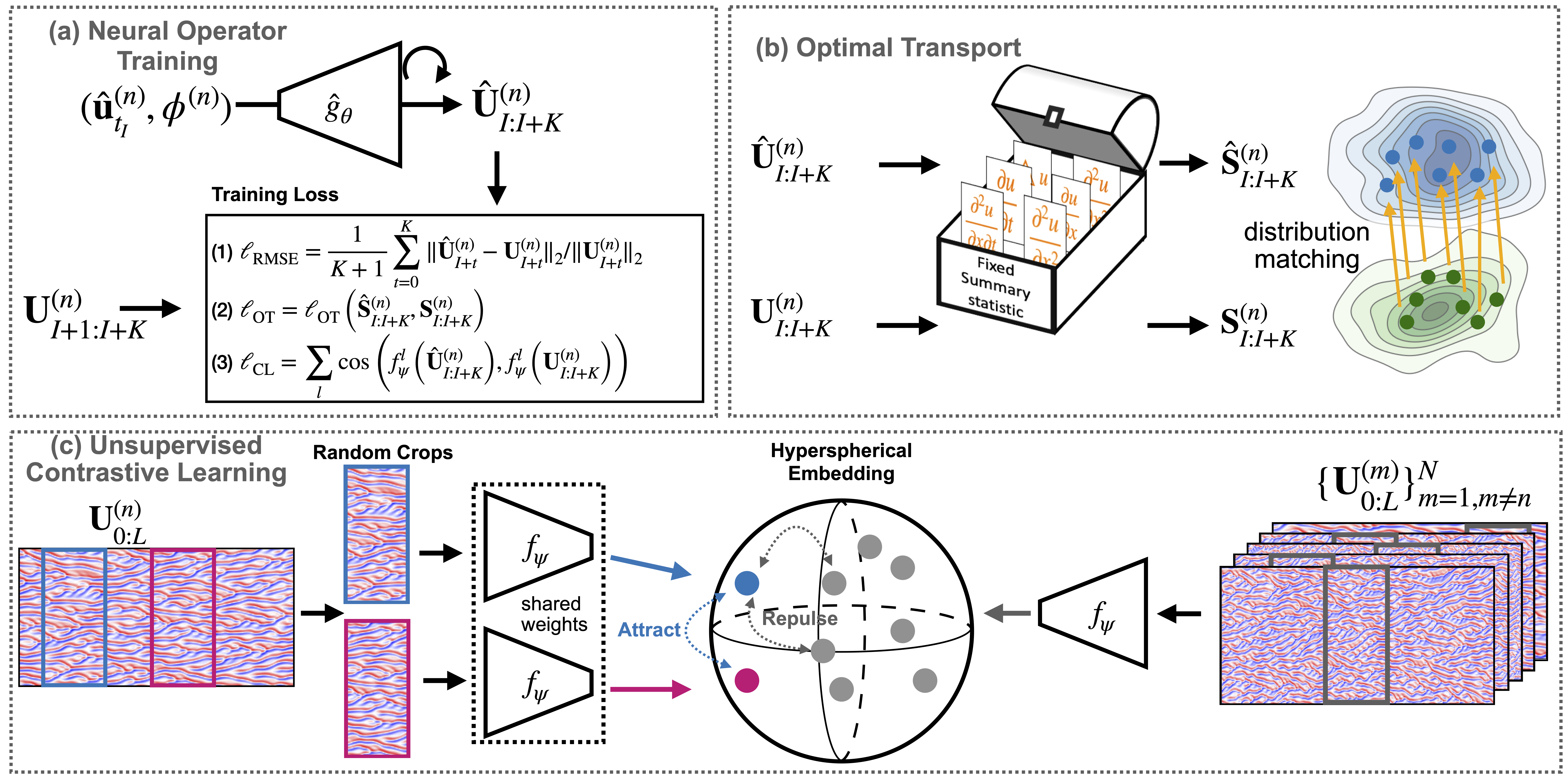

We address this problem by developing new training methods that encourage the emulator to match long-term statistical properties of the chaotic dynamics—which, again, we refer to as the chaotic attractor. We propose two approaches for achieving this:

-

Physics-informed Optimal Transport: Choose a set of relevant summary statistics based on expert knowledge: for example, a climate scientist might pick the global mean temperature or the frequency of hurricanes. Then, during training, use an optimal transport metric—a way of quantifying discrepancies between distributions—to match the distribution of the summary statistics produced by the emulator to the distribution seen in the data.

-

Unsupervised Contrastive Learning: Automatically choose relevant statistics that characterize the chaotic attractor by using contrastive learning, a machine learning approach initially developed for learning useful image representations for image recognition tasks and generative AI. Then, during training, match the statistics of the emulator to the statistics of the data.

The distinction between the two methods lies primarily in how we choose the relevant statistics: either we pick (1) based on expert scientific knowledge or (2) automatically using machine learning. In both cases, we train emulators to generate predictions that match the long-term statistics of the data rather than just short-term forecasts. This results in much more robust emulators that, even when trained on noisy data, produce predictions with the same statistical properties as the real underlying chaotic dynamics.

The best we can hope for when modeling chaos is either short-term forecasts or long-term statistical predictions, and emulators trained using the newly proposed methods give us the best of both worlds. Emulators are already being used in a wide range of applications such as weather prediction, climate modeling, fluid dynamics, and biophysics. Our approach and other promising recent developments in emulator design and training are bringing us closer to the goal of having fast and accurate data-driven models for complex dynamical systems, which will help us answer many basic scientific questions as well as solve challenging engineering problems.

Please see our paper for more details.